Working in conjunction with Edge Hill University on their ‘multispecies storytelling project’ got me thinking about how we treat the land that feeds us, together with the nature we share it with.

Neil Hickson

It’s a dream of many people, owning a piece of land. Think of it, owning your little piece of the globe and doing just what you want with it. The possibilities are intoxicating. Grow food, lie in the long grass, plant trees, make ponds, rent it out, graze animals, live on it, camp on it, have fun with it. But, you soon realise, owning land is a big responsibility.

Farmland is precious, it’s where we grow food. You can make money out of it; well, some money. You won’t make a fortune though and growing food for a living is tough going.

Back in 2013, all these ideas spun through my head. We had become landowners, rulers of our domain. We could do what we want (within the limits of the planning laws), but what’s the best thing to do?

No sooner do you own land than you realise, it isn’t yours at all. You are a custodian for something that will be here long after you have gone. All you are is an influencer, someone who helps decide what happens next in the story of that land. In the end, it is owned by nature and nature will eventually formulate its own outcome.

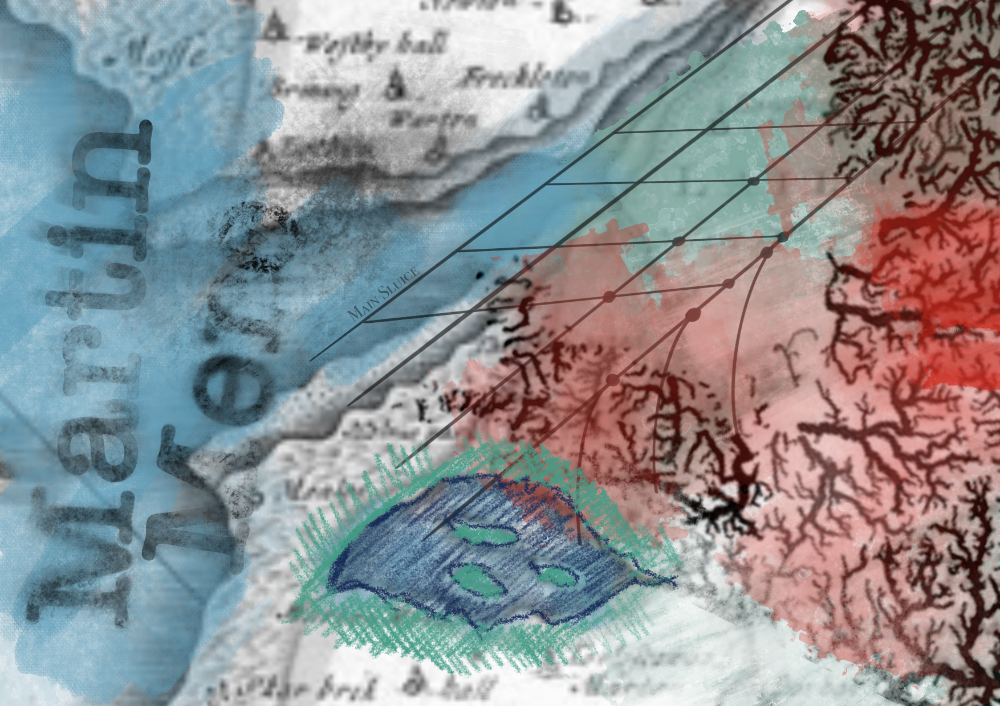

The land we farm is low-lying. It was a peat bog, part of Martin Mere, once the largest inland lake in Europe. However, the land was drained a few hundred years ago. It’s now cross-crossed with a complex network of drainage ditches that keep the land in a farmable condition.

This area is some of the best farming land in the country. For example, it’s one of the few places in this nation where you can grow carrots really well. The West Lancashire plain was first exploited to feed the industrial cities and towns of the region. Liverpool and Manchester were fed by this land and we send our produce to Manchester market to this day.

But there are problems in our area. The government now wants to save money by switching off some of the satellite pumps that support farming. These relatively small automatic pumping stations drain pockets of the land, putting water into the larger drainage system that is ultimately pumped out to sea at Crossens, just outside Southport.

Without continuous pumping, this land will become increasingly saturated. It will become unfarmable, and then where will we grow our food? I say ‘our food’ because it’s your food; you are just as much of the problem as I am.

Should this land return to nature? Peat bog is an amazing storage medium for carbon, far better than trees. But, to create peat bog you need to accumulate water.

As well as being part of a peat bog, our land is also a conduit for water. Like it or not, we are part of a drainage system and our neighbours rely on us keeping our ditches clear so their water has unfettered access towards the sea through our land. Restricting their water flow would leave us liable to prosecution.

The more farmers use what is now regarded as conventional methods of farming including ploughing and turning over the soil, the more rapidly the peat, which gives the land its amazing fertility, will oxidise and shrink. Couple this with larger fields, lack of hedgerows and increased wind erosion and farmers are the architects of their ultimate failure.

Within the last few years I can think of at least two occasions where massive dust storms blew across the West Lancashire Plain stripping valuable top soil.

Modern farming techniques have created an abundance of cheap food that fills the shelves of our local supermarkets. Spending your money drives the tractors.

At Burscough Community Farm we are trying to do something different. We have planted thousands of trees. We are now experimenting with a ‘no-dig’ method of farming which is literally putting carbon back into the soil. We are working on a small scale, but I’ve proved to myself that we can be very productive. We rely on a lot of hand tools and human labour to grow our produce, so our farming is very much on the human scale.

I’m not saying I have all the answers, we haven’t been able to make the farm provide a reliable income yet. One of the reasons for that lies in another problem, the kind of problem that has sometimes kept me awake at night.

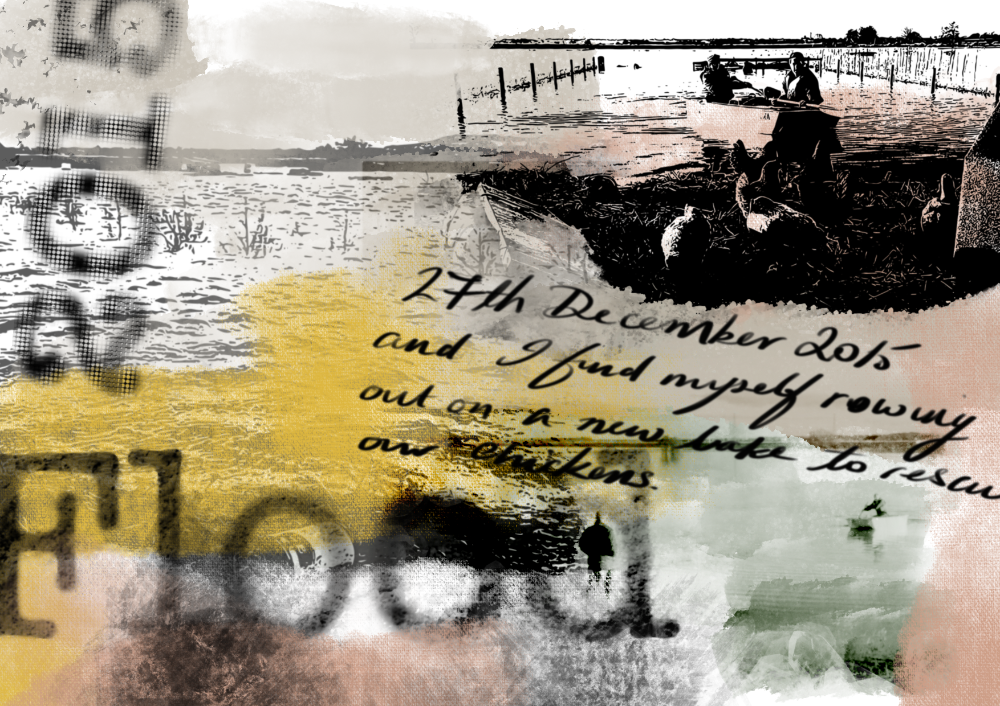

Back in 2015, 26th of December, Boxing Day, we had some of the heaviest and most persistent rain I’ve ever seen. It rained so much that I couldn’t even take my wife to work in Preston in the car. Roads were flooded all around us and across the county.

It was a massive rainfall event compounded by a high tide. The outcome? The normally passive Eller Brook, a large ditch which usually trickles past our farm, had risen to the limits of its bank, three metres above our field. The water washed over the top of the bank, weakening it and eventually causing it to collapse. The result put us nearly six feet under water and created a mile-long lake which we rowed out across in boats the next day. We thought it was the end of our farming journey, but in the next growing season we produced our best ever crops.

Is this just nature fighting back and reclaiming what is hers? Maybe, but there are other elements to this story.

One factor in this disaster was the increasing pressure being put on the drainage system in our area. New housing projects upstream with their impenetrable roofs, driveways and roads mean that when it rains, that rainfall reaches us increasingly quickly. In the past, such rain would be soaked up by fields, trees and hedges, then slowly percolate through the ground to eventually drain past us. Now, it rapidly reaches the ditches, brooks and rivers, overwhelming them, and flooding us.

It’s a solid fact in the laws of drainage that once water leaves your land, it is no longer your responsibility. And here’s another fact. Your downstream neighbour has no right to impede the water flowing off your property, to do so would be breaking the law.

With climate change and the likelihood of ever-increasing and more ferocious storms, we must accept that flooding is going to be a more frequent part of our lives. Will this ultimately mean the end of farming in our area though?

Throughout all this essay, I’ve talked about the land as if it was just a resource for us to use for our own ends. This land is designated as farmland. We’ve been reminded many times this is how the planning authorities see it and you have a big job on your hands if you want to use it for anything else. Even returning the land to nature by calling it a nature reserve would need planning permission. It seems although the government doesn’t want to fund drainage of the land and support farming, part of their bureaucracy regards farming as the land’s only mission.

There are of course a lot more stakeholders in this piece of real estate we call Burscough Community Farm. For a start, we are a ‘not for profit’ community farm, open for all the community to join us and grow food.

The flora and fauna that increasingly occupy our farm also deserve their say. They don’t have voices to represent them, they just soak up what’s thrown at them and try to adapt to live in the places where they can scratch out an existence.

We have big plans for nature on our land. Using Permaculture farming methods inform how we work with nature so we both have room to live together. Nature takes every opportunity it can to prove its resilience to our efforts because we farm organically. Believe me, nature puts up a good fight.

The areas we plan out and leave as habitat for our pest predators seem to reward us with little competition for our crops from other species. But weeds, they are another matter. Weeds are a constant adversary in our battle to grow food. The land we occupy would quickly return to woodland if we didn’t take steps to keep control of the areas where we want to grow food. Self-seeding trees that started to grow when we took over managing the land in 2013 are now over four metres tall.

We are a little oasis for nature surrounded by a monoculture of food crops. And there’s the rub. Farmers use the land all around us to efficiently fill your local supermarket with the things you love to eat. But they do so at the expense of an alarmingly worrying decline in species. Plants, insects, birds and mammals have less and less habitat to survive. The red list of endangered species continues to grow.

So, I return to my original question, ‘who owns this land?’ Should the question not be about ownership at all, because, in a way we all own it, and it, in turn owns us.

How we talk influences how we think. And how we think changes what we do. None of us can carry on treating the land as we do at the moment.

If we don’t change our ways, the land will change them for us.

Words and images by Neil Hickson © 2021